Christmas and its music has long occupied a cultivated plot — squarely in a favored corner of my personal musical landscape. This is true because our Mother and Father always made Christmas such a happy time—now, with still-vivid and wonderful memories of our departed Mother and Father.

My first recording of Christmas music was circa 1982—and, was my re-arrangement of vocal and instrumental parts from the Christmas cantata that had been performed by our choir at Epworth UMC (Huntsville, AL, USA), where I was then organist. I later lost the only version of that recording. I save that story for another post.

It was not until 1996 that I recorded another Christmas project. While I lived in St. Louis, MO, USA (1996-1998) I accompanied the annual Christmas employee hymn-sing at the (then) Defense Mapping Agency (DMA), (later, NIMA, now NGA). The recordings that I made for these services became the 2001 “O, Come Let Us Adore Him” project.

By 2001, I had upgraded my recording studio, audio equipment, and the Macintosh IIsi computer (with upgraded processor card) that I was using while in St. Louis. The new Mac (Beige) G3 “purred” through 2001’s project. All of the arrangements are instrumental and feature sounds from my then-also-new Kurzweil K2500X keyboard synthesizer. The CD art is a photograph taken by me in the darkened library of my parent’s house, of the Nativity scene they acquired in Jerusalem.

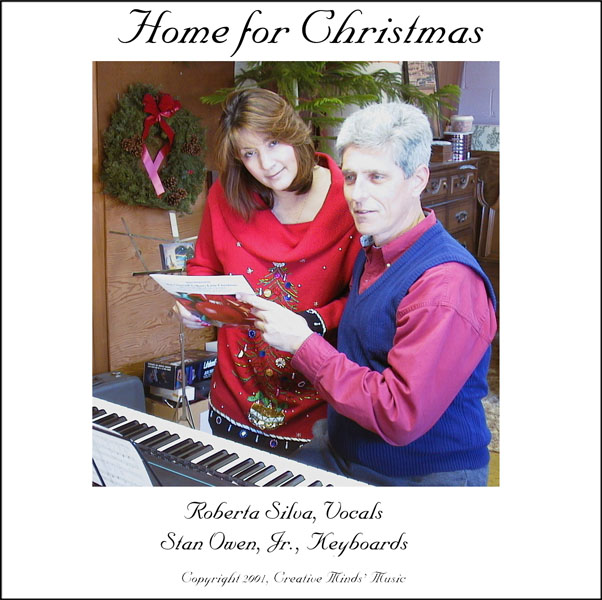

That same year (2001), I was fortunate to resume my long-time, musical association with my colleague, vocalist-extraordinaire, Roberta Silva. Roberta and I worked together professionally several times over the years. My favorite Christmas projects are the ones that feature performances by Roberta. Our 2001 collaboration produced “Home for Christmas.” Roberta’s work on this CD includes several memorable performances, including my favorite: “Let There Be Peace On Earth.”

I’m not sure what prevented the 2002 Christmas project. But, our next project, “Home For the Holidays” was 2003’s endeavor. I’m particularly fond of Roberta’s rendition of “Favorite Things.” In 2003, I also began my long-term project to orchestrate all the pieces of the Nutcracker Suite. After arranging the first piece, the “Overture,” I realized that my goal to orchestrate the entire Suite would not be accomplished in a single year. So, I finished that year’s project by recording the majority of the Nicholas Economou piano-duet versions of the “Nutcracker.” The Nutcracker used for this CD cover-art, is a photo of the Nutcracker given to me by a former music-student. Earlier that year I had begun to experiment with 3D (graphics) modeling. The CD art, including the Christmas tree with modeled ornaments, are my original 3D graphic artwork, authored using the Bryce 3D graphics modeling program.

In 2004, I was unable to schedule time to record with Roberta and decided to produce a piano-only Christmas program. “Christmas At The Piano” was the result. I am still particularly fond of Victor Herbert’s beautiful song, “Toyland” which is featured. The CD cover-art is more of my early 3D-graphics modeling.

I was apparently pressed for time during the 2005 season—and, included only three selections that in that year’s project: “Christmas Master Pieces.” Both Bach arrangements are my re-arrangements of often-performed E. Power Biggs organ arrangements. The arrangement of Handel’s “Hallelujah” is mine—and, uses strings and synthesized-brass in place of the customary vocal parts. The CD art was my rendition of myself with a beard—before I actually grew one. The keyboard graphic is a stylized photo of my Kurzweil K2500 keyboard.

The 2006 Project, “Memories of Christmas” featured 20 pieces from previous projects; and, was a retrospective that featured my favorite selections from the past years’ performances. The CD cover features a photo of me with (real) long hair, beard, and visions of sugar-plums.

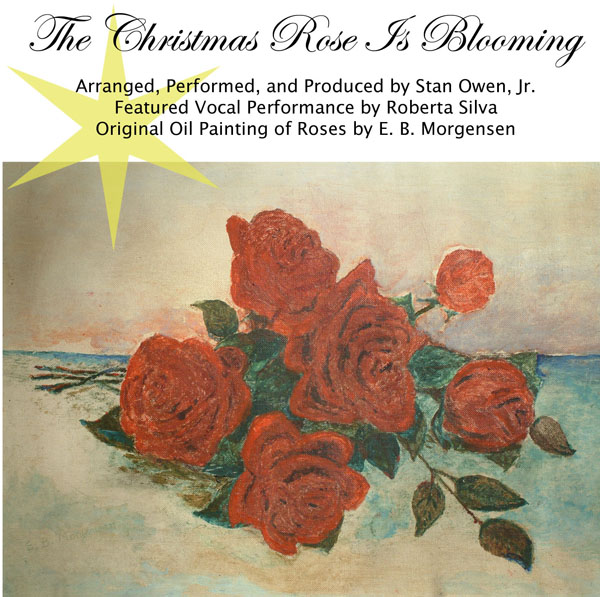

The 2007 Project, “The Christmas Rose Is Blooming” featured a beloved painting of roses that was painted by my maternal-grandmother, Emma Breck Morgensen. The story of this painting and its return to me, will eventually become the subject of a blog post. That project features several arrangements by me, of well-known Christmas songs and carols, several additional original Nutcracker orchestrations, and a rearrangement of a previous year’s recording of “The Little Drummer Boy” that added harmony-vocal parts to Roberta’s original performance of the tune. This project featured my first use of the orchestral software: “Synful Orchestra” that I now call my “secret weapon.”

“The Spirit of Christmas,” 2008 project featured several additional original Nutcracker synthesized orchestrations and includes the single Nicholas Economou Nutcracker piano duet that I had not recorded in 2003. Most notable in this project is Roberta’s performance of my transcription of Dave Grusin’s beautiful arrangement of the Hutson-Burt song, “Some Children See Him.” Working with music manuscript paper, pencil, and lots of erasers, I transcribed the piano and string parts mostly note-for-note from the James Taylor CD. The digital painting of Santa is an original work by this more-musician-than-artist.

2009’s project, “Simply Christmas” featured three pieces. The first is a piano arrangement from the old, now-defunct Etude music magazine that I played as a child. Additional information about the Etude music magazine will become another post. The second piece is another in my ongoing series of Nutcracker orchestral synthesizer arrangements. The final piece is a beautiful performance by Roberta Silva of Gustav Holst’s Christmas carol, “In The Bleak Midwinter.” The arrangement is another of Dave Grusin’s arrangements that I transcribed for this project. The CD art features re-purposed pencil sketches of bells and ribbons that I originally drew for the “Wedding Dedication” CD, but didn’t use, then…

2010’s project featured my final installment of original, synthesized Nutcracker orchestrations including orchestrations of Russian Dance, Arabian Dance, and Chinese Dance. Additionally, this version of the Nutcracker Suite re-records several previously recorded pieces—one work, rearranged to use current instruments (Overture), and four arrangements from previous years’ projects that I have revised and re-recorded this year to ensure consistent instrumentation and acoustic space.

For 2011’s project, Roberta and I again teamed to record two Christmas classics: I Wonder As I Wander and Do You Hear What I Hear?

For 2012’s project I chose five (5) carols that each have a long and rich history. The youngest of these pieces was written in 1868. As I worked on my annual labor-of-love, I thought often of my Mother, whom we lost in 2012 – and, who likely first taught me each of these pieces. For this reason, I decided to use one of her paintings as accompanying art. Three of the arrangements are mine and the other two are pipe-organ arrangements that are more fully-described in the related blog-post.

For 2013’s project I arranged Harold DeCou’s “Christmas at the Keyboard” for synthesizer. My performances are re-orchestrations using original, customized Kurzweil PC3K8 programming.

2014’s project, “Christmas Creations for Two Pianists” is a series of 11 short piano-duets that my Mother and I, and later, my sister, Cathy and I played. I dedicated 2014’s project to the memory of our dear and precious Father, who left us on December 16, 2014. He was our inspiration, encourager, and greatly enjoyed hearing us play these arrangements for him.

2015’s project, “Memories of Christmas, Volume 2” is my second collection of recordings from previous years’ projects. Volume 2 collects all of the recordings that Roberta Silva and I made since Volume 1.

In 2016, I re-arranged and recorded Selections from “A Dave Brubeck Christmas,” for synthesizer. For several years I wished to record this collection of Dave Brubeck’s Christmas improvisations/arrangements. Brubeck has been a longtime favorite of mine and I have benefited greatly from the study of several Brubeck pieces that I have performed over the years.

My Christmas project for 2017 was not a Christmas project at all. I completed and posted Twenty-Three Early American Folk Hymns Arranged for Organ mid-November. At that time I began the Christmas project I had planned. However, because of technical problems in my studio earlier in the fall and because of the limited time remaining until Christmas, I decided to enlist the American Folk Hymn project as 2017’s Christmas project.

For my Christmas 2018 project, I resumed the project I postponed from 2017. However, because of again beginning work too late, I decided rather than to redo all of the recordings from 1998’s “O, Come Let Us Adore Him” project as I had planned, that I would make a medley of the pieces. The medley became 2017’s Christmas project: “Happy Birthday, Jesus.”

I hope that you enjoy these Christmas music projects from years past. Merry Christmas and Season’s Greetings!

For a long time I wanted to use my synthesizers to produce a whistling version of the “Andy Griffith” television show’s musical theme-song.

For a long time I wanted to use my synthesizers to produce a whistling version of the “Andy Griffith” television show’s musical theme-song.

Recent Comments